Nine days into June and we’ve already had our second heavy rainfall event. Our first was 4 inches in 48 hours, and after a few days off and 90+ degree temperatures, we just got another two inches. In an average year, we see 3-4 inches in the entire month of June, and highs around 75.

This month we’ve gone back and forth between a few days spent getting heatstroke planting the garden, and then watching it flood out with heavy rains, then repeat. All our holding ponds are full and overflowing, and there’s standing water everywhere.

The forecast for the next 10 days? More heat, alternating with significantly more rain. On the plus side, at least we’re not in drought like much of the rest of the country. It doesn’t seem like drought is in our future, short term or long.

Both long and short term climate forecasts for our region predict more of the same: warmer and wetter.

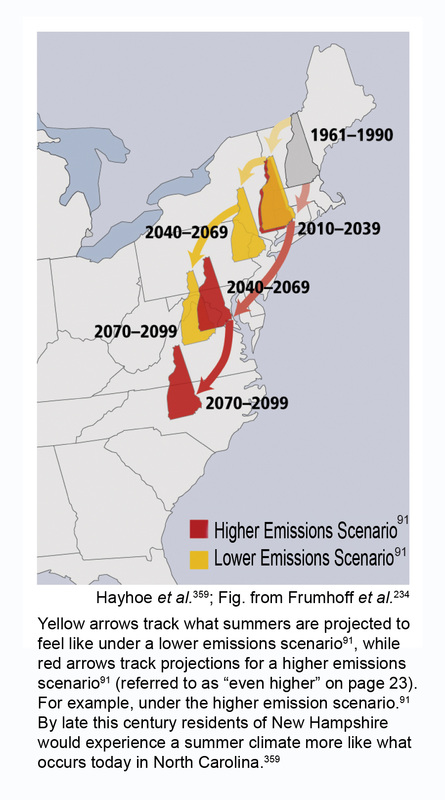

The most recent national climate assessment released in 2014 shows that in the past 100 years temperatures have increased by an average of 2 degrees, and rainfall has increased by 5 inches per year (10%). Over the next 100 years, temperatures will increase an average of 3-10 degrees and we’ll see another 5-20% increase in precipitation.

In our lifetime, summer in Northern New England is predicted resemble a summer in North Carolina. Even if climate change is substantially curbed by reduced emissions, we’re still looking at at least Northern Virginia summers before this century is out.

On the bright side, perhaps we’ll be able to grow peaches in the near future, and maybe we’ll be zone 5 before long. More practically, it means we need to work to establish rainwater management systems to reduce flooding and runoff.

The most concerning part is the incidence of heavy rainfall events has already begun to increase. In the last 50 years, extreme precipitation events have increased by 70%. Good examples include hurricane Sandy and Irene.

On our homestead, we’ve begun working on measures to slow water movement across our land and thereby reduce erosion. Keeping the soil covered with cover crops and mulch helps absorb some of the initial rain, but once the soil becomes saturated the water needs a place to go, but go slowly. Channeling water too quickly creates erosion and results in topsoil loss, which is bad news for crops. Creating efficient drainage ditches, slowed by small holding ponds, helps us channel water off the land, while keeping erosion in check.

Raised beds help keep our plant roots above the saturation, and help raise soil temperatures early in the year thereby extending our growing season. Using cord wood to build the raised beds further helps buffer excessive rainfall, as the cord wood absorbs and holds a substantial amount of water.

The next step is to get cover crops established in the aisles to absorb additional moisture and help prevent the soil from washing away. We’ve already begin mulching some areas to get the soil covered, but we cant make chips fast enough to keep up with the demand all the new plantings put on our mulch supply.

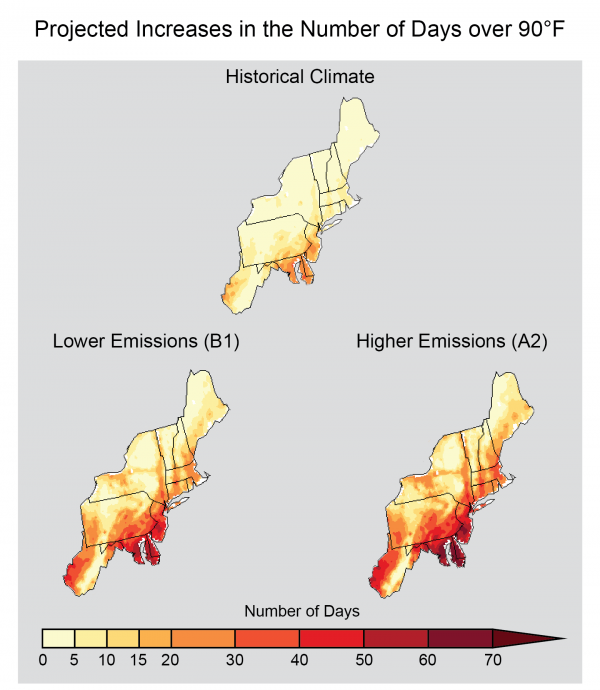

Increased temperatures are another issue to be tackled. We live in a cool climate, so unlike western states, we have quite a bit of buffer room to absorb additional warmth. Days above 90 degrees are projected to increase in the summer, but summer highs are not as much of a concern as winter thaws. Increased temperature variability, especially in the winter, can be disastrous for perennial crops.

In the past few years we’ve already seen mid winter thaws that caused grapes to break dormancy early, thus killing them when temperatures plunged again. Heat waves in March cause fruit trees to break bud and flower early, and the fruit crop is destroyed when temperatures drop back below freezing.

Thaws also remove the insulating snow cover that prevents extreme cold from killing perennials. Ironically, winter thaws mean plants that were previously hardy in our area may be killed by temperatures they previously would have survived had snow cover been present.

The best protection against this, contrary to intuition, is to plant in colder areas that receive shade during the winter. If the ground stays frozen and the air cooler during winter hot spells, the plants are less likely to break dormancy.

Our homestead still has quite a bit of work to do to adapt to the changes before us. At least for now, time is on our side. While this change is happening rapidly on a geological time scale, it’s still happening slowly on a human scale. We may never be able to plant mango trees outdoors, but Ginger is already being grown profitably in Maine and other Northeast states. The changes are small each year, but if we can keep our homestead above the water with all the extra rain, in a few decades who knows what else we’ll be able to grow.

Sources:

USGCRP (2009). Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States .

USGCRP (2014). Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment

Columbia University (2014). Northeast Already Hit By Climate Change, Says Major US Report